Introduction

The Left wants sweeping changes that tie loan payments to income and forgive large amounts of debt. The Right wants to end mass forgiveness and make colleges pay when their graduates cannot. Either way, student debt is not going anywhere, and it has become one of the defining financial issues in the United States. Many borrowers face a decades-long anchor that shapes every major decision, from where they live to whether they have children. Others see it as evidence that higher education has shifted from being a mission-driven public good to a revenue-driven enterprise. Colleges today often operate with the priorities of for-profit corporations, focusing on maximizing revenue and lobbying for expanded federal loan access, rather than focusing primarily on providing high-quality, affordable education.

The debate is political, economic, and deeply personal. This paper examines the growth of tuition costs since the 1980s, the total amount of outstanding debt, the interest rates students face, and how much they actually repay over the life of a loan. It also outlines the views from the political Left and Right before presenting a middle-ground solution.

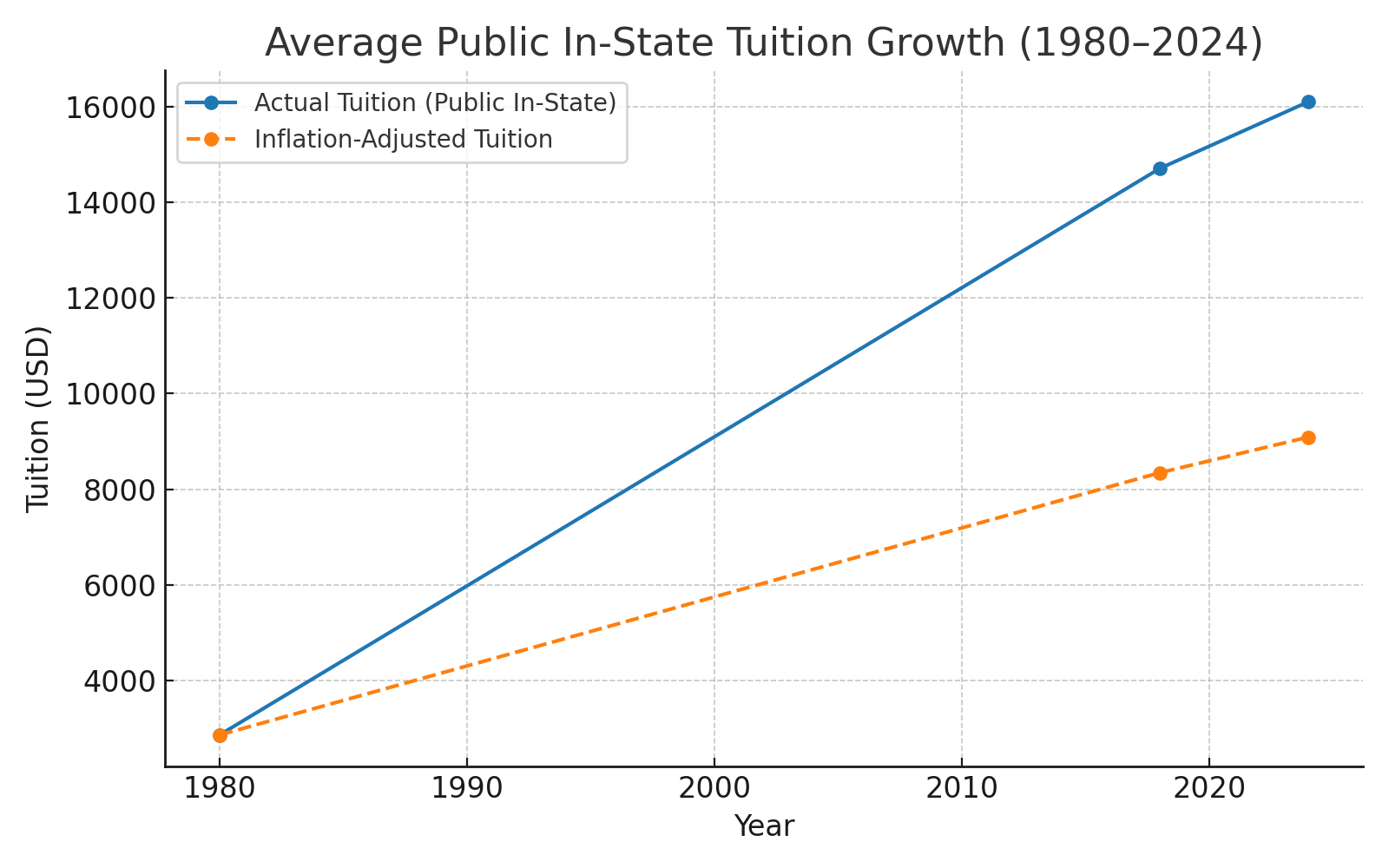

The Rising Cost of College Tuition

College tuition has increased far beyond the pace of inflation and wage growth for more than forty years. A full-time worker earning the median wage in 1980 could cover tuition at a public university with about two months of pay. Today, covering tuition and basic living expenses for the same degree can take more than six months of gross earnings.

In 1980/81, in-state tuition and fees at public four-year institutions averaged $2,855 per year in today’s dollars. By 2018/19, that figure had risen to $14,715. If tuition had risen in alignment with inflation, the total should only have amounted to $8,345.

The trend has not slowed in recent years. In 2023/24, in-state tuition and fees ranged from $6,360 in Florida to $17,180 in Vermont.

For 2024/25, national averages from the College Board show:

- $11,610 for in-state public four-year

- $30,780 for out-of-state public four-year

- $43,350 for private nonprofit four-year

When factoring in tuition, fees, room, and board, the total budget for an in-state student at a public four-year school now averages $29,910.

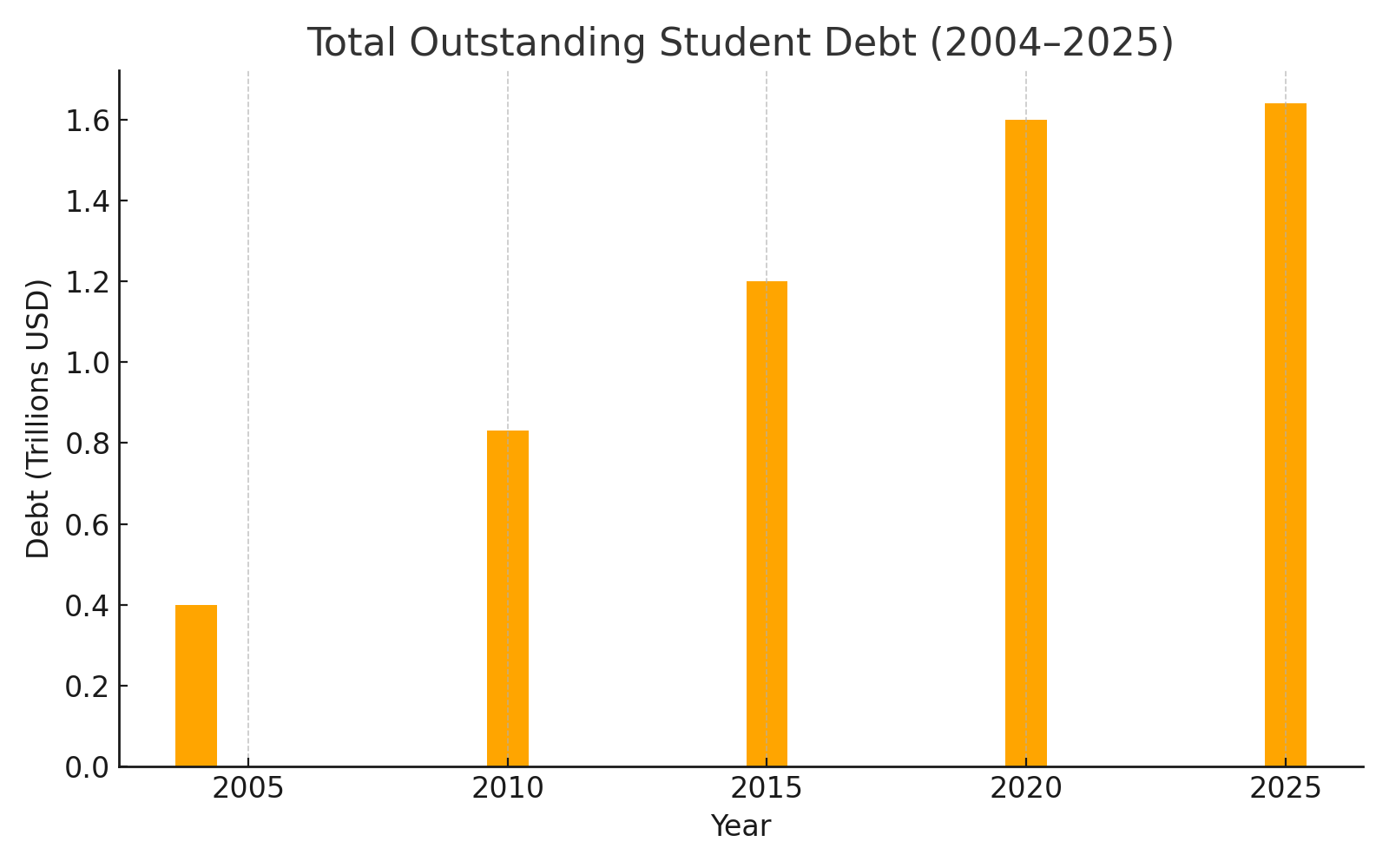

How Much Student Debt Exists

Student debt is now a permanent fixture in the national balance sheet. As of the second quarter of 2025, Americans owed $1.64 trillion in student loans. The share of borrowers at least 90 days delinquent is 10.2 percent.

For federal student loans, the lender is the U.S. Department of Education, meaning taxpayers are ultimately on the hook if a borrower defaults. The federal government guarantees these loans, so when they go unpaid, the cost is absorbed by the federal budget, increasing the burden on taxpayers. Private student loans, which make up a smaller portion of the total debt, are the responsibility of the private lender, although default can still have severe consequences for the borrower.

In 2004, the total outstanding student loan balance was under $400 billion. Today’s figure is more than four times that amount, with a borrower base of about 43 million people.

Average Interest Rates

Interest rates on federal student loans are set annually and vary by loan type. For the 2025–26 academic year, the rates are:

- 6.39% for Direct undergraduate loans

- 7.94% for Direct Unsubsidized graduate loans

- 9.94% for PLUS loans

In 2020/21, undergraduate loans carried an interest rate of just 2.75%. Higher rates mean significantly larger total repayment amounts, especially for long-term loans.

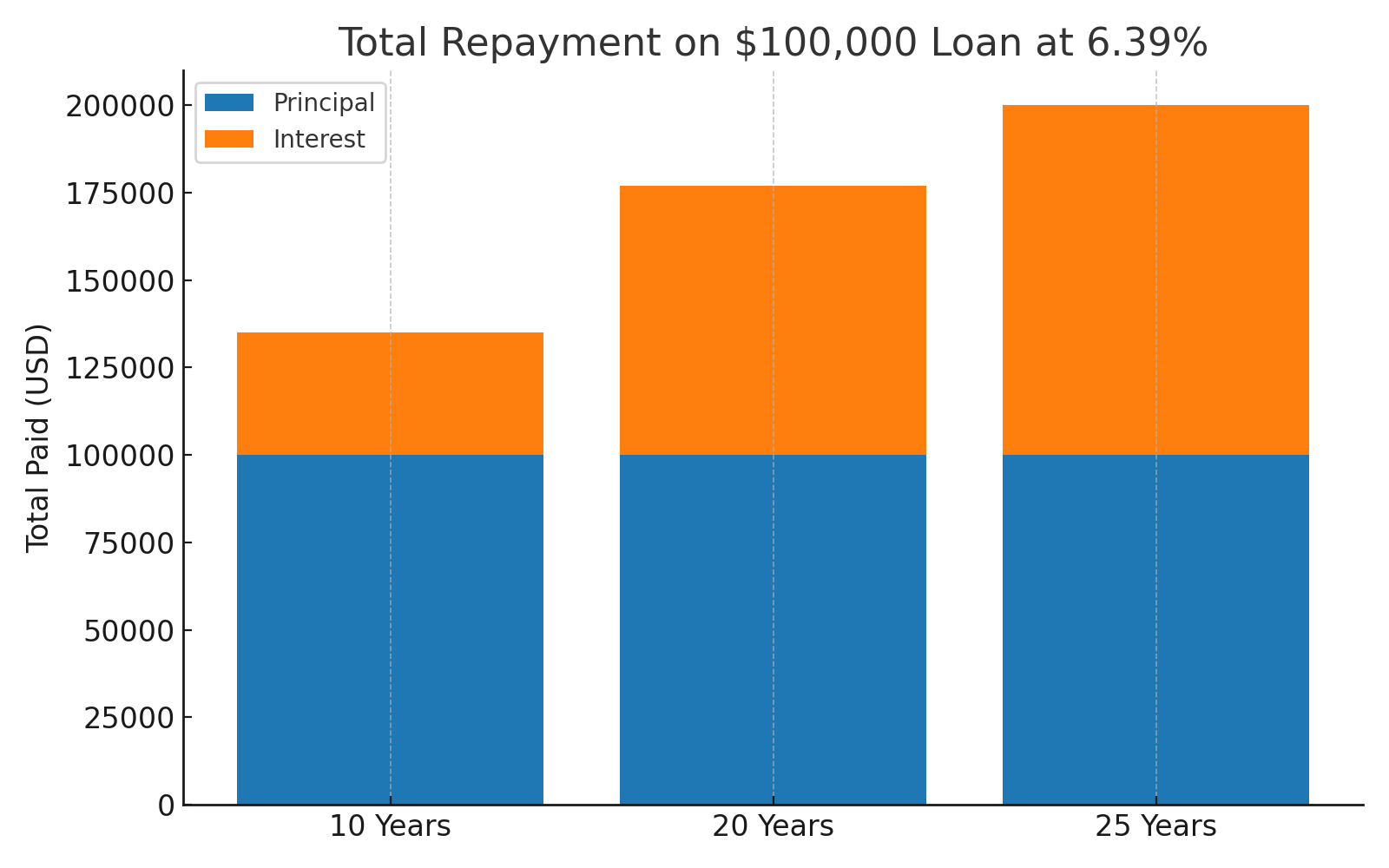

How Much People Really Pay Back

A 6.39% undergraduate loan rate on $100,000 might sound like it means roughly $6,000 in interest. That is not how student loans work. Interest on most loans begins accruing as soon as the funds are disbursed, not after graduation. For unsubsidized loans, this means the balance can start growing while the borrower is still in school. If unpaid interest is added to the principal (capitalized), future interest is charged on that larger amount.

This is the effect of compound interest. Under a standard 10-year repayment plan, a $100,000 loan at 6.39% will accrue about $35,000 in interest, making the total repayment roughly $135,000. Extend the repayment period to 20 years, and the interest climbs to about $77,000 for a total near $177,000. Go to 25 years, and the interest alone can top $100,000, pushing the total repayment toward $200,000. The longer it takes to pay, the more the compounding works against the borrower.

The Left / Democratic / Liberal View

Many Democrats and progressive policy groups view student debt as a structural problem that requires systemic reform. Their core positions often emphasize making repayment affordable, protecting vulnerable borrowers, and targeting relief where it is most needed. Key policy elements include:

- Expanding income-driven repayment (IDR) so payments are tied to a borrower’s income, capping them at a manageable percentage, and forgiving any remaining balance after 20–25 years.

- Strengthening borrower protections, such as halting interest accrual for low-income borrowers, limiting interest capitalization, and expanding options for deferment or forbearance without severe penalties.

- Implementing or preserving targeted debt forgiveness programs for public service workers, borrowers defrauded by schools, or those facing extreme hardship.

- Increasing accountability for colleges, particularly for-profit institutions with poor graduation rates or weak job placement records, by tightening accreditation standards and linking federal aid eligibility to performance outcomes.

- Supporting tuition-free or debt-free community college programs and increasing federal and state investment in higher education to reduce the need for borrowing.

The Biden administration’s SAVE plan reflects this philosophy, reducing IDR payments to as little as 5% of discretionary income for undergraduate loans and raising the income exemption to 225% of the poverty line.

Advocates argue that this approach prevents borrowers from being crushed by monthly payments, ensures predictable timelines to forgiveness, and promotes upward mobility by reducing financial stress.

The Right / Republican / Conservative View

Many Republicans and conservative policy groups frame mass cancellation as unfair to taxpayers and harmful to price discipline. The focus rests on limiting federal lending that fuels tuition inflation and making colleges share the risk when graduates cannot repay.

Core positions include:

- Scaling back federal student lending, especially programs that allow borrowing beyond expected earnings capacity. Supporters argue that easy credit encourages schools to raise prices instead of cutting costs.

- Risk-sharing for colleges. Institutions would repay a portion of defaulted or non-repaid loans when their graduates perform poorly on repayment metrics. Penalties could include direct financial liability, loss of eligibility for federal aid, and forced closure of consistently low-performing programs. The aim is to push schools to control tuition, improve program quality, and align curricula with labor market demand.

- Outcome transparency. Colleges would publish clear program-level data, such as graduation rates, median earnings, debt-to-earnings ratios, and repayment rates, so students see value before enrolling.

- Alternative pathways. Policy favors trade schools, apprenticeships, military service training, and community colleges that deliver skills with lower debt loads.

- Guardrails on repayment plans. Proposals often call for limiting overly generous income-driven terms that allow growing balances, in order to reduce long-run costs and moral hazard.

- No broad forgiveness without Congress. The view holds that large write-offs require legislation, not executive action, citing the Supreme Court’s 2023 ruling against the HEROES Act attempt.

A Middle-Ground Proposal

A practical solution would cap the total repayment amount at 15% above the original loan principal. A borrower who takes out $100,000 would never pay more than $115,000 in combined principal and interest. This cap would apply regardless of repayment term, pauses, or deferments. The policy would prevent decades of crushing interest without fully removing borrower responsibility, striking a balance between fiscal responsibility and borrower protection.

Conclusion

Tuition has risen faster than wages, and student loan balances have climbed into the trillions. The Left emphasizes income-based repayment and forgiveness. The Right emphasizes reducing federal lending and making colleges financially responsible. A 15% repayment cap offers a middle path that ensures repayment while preventing borrowers from being crushed by decades of interest.