Everyone knows the rule of thumb: do not buy a house more than three times your annual income. It has been around for decades, passed down like gospel. The problem is that rule only works in a world where wages and home prices move in step with each other. That world does not exist anymore.

I am making this as a response to a creator on TikTok who said the minimum wage would need to be sixty-six dollars an hour to afford a median priced home. The problem here is that he is mixing apples and oranges. He is taking the very bottom of the wage table and comparing it to the middle of the housing market. That is a misleading comparison today. Here is what the numbers look like:

- Minimum wage today is $15,080 annually

- 3× minimum wage salary equals $45,240

- Minimum wage at $15 is $31,200

- 3x $15 minimum wage is $93,600

- Median full-time single-earner income is $60,070 annually

- 3× median single-earner income equals $180,210

- Median home price is $443,471

The median home price being $443k, actually means half the homes are less than that price. Given all the different statistics, this analysis uses $443,471, but the number could be off depending on which source you wish to cite.

Now that we are dealing with facts, we can already identify a major issue. Someone earning minimum wage has absolutely no chance to purchase a home, unless they are extremely lucky and they live in an area where $45,000 homes still exist. Worse still, a person earning the median full-time single earner income is only able to purchase homes in the $180k range, and that is only a possibility with good established credit and no other debt. For a median earner to purchase a median house is 7.38 times their annual salary.

This alone tells a story. We do not have to reach back to any other era of American history to see how broken affordability is today. Yet people often want to make a comparison. They ask if it really was better for the Boomers. That question deserves a clear answer.

Was it better for the Boomers?

The creator claimed the minimum wage would need to be sixty-six dollars an hour today to give workers the same buying power Boomers had. That claim comes from looking back on 1968, when a single minimum wage worker could realistically afford a median priced home. Here are the facts from 1968:

- The federal minimum wage was $1.60 per hour

- 3x minimum wage salary equals $3,300 per year

- Median full-time single earning income was about $7,700 per year.

- 3x median single-earning income equals $23,100

- The median home price was about $25,000.

Buying a median home on minimum wage alone would have required about 7.57× annual 1968 minimum wage income.

Buying a median home on minimum wage today would require 29.4 times the annual 2025 minimum income.

At face value, the ratios look different depending on which benchmark you use.

Minimum wage to median home price In 1968, a median home cost about 7.57 times annual minimum wage. Today, a median home costs about 29.4 times annual minimum wage. Median income to median home price

In 1968, a median home cost a little more than 3× median household income.

Today, a median home costs about 7.3× median single-earner income.

The surface-level comparisons make it clear. In 1968, minimum wage was much stronger relative to household earnings, and homes were much cheaper relative to income. A minimum wage worker earned about 43 percent of median household income. Today, minimum wage equals only about 19 percent of median household income.

Mortgage rates add another layer. In 1968, the average 30-year mortgage carried an interest rate of 7 percent on a $25,000 home. Today, mortgage rates again sit between 6 and 7 percent, but they apply to homes costing $443,000. That financing burden alone explains why home ownership is far less accessible for today’s workers than it was for Boomers.

What if we reset everything?

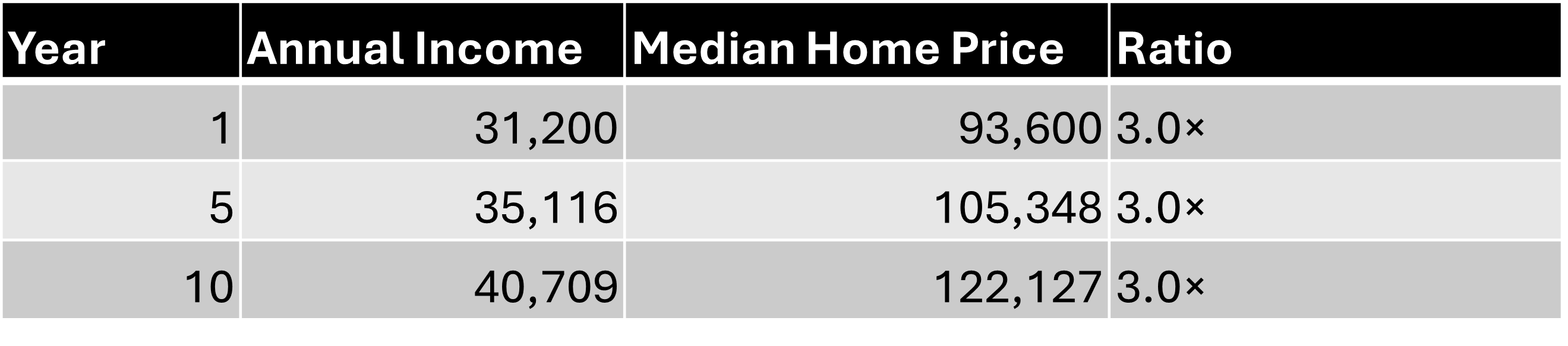

Let us reset the table. Imagine in 2025 we give workers what they want: fifteen dollars per hour minimum wage. That equals $31,200 a year at full-time work. Using the three-times rule, the affordable home price would be $93,600. Saving 20 percent of income each year, a worker could put aside $6,240 and reach the down payment target in about three years. Saving 35 percent by cutting discretionary spending would shorten that to less than two years.

So far, so good. Now add inflation. If both wages and home prices rise at three percent per year, the ratio stays steady. In this model, workers never fall behind.

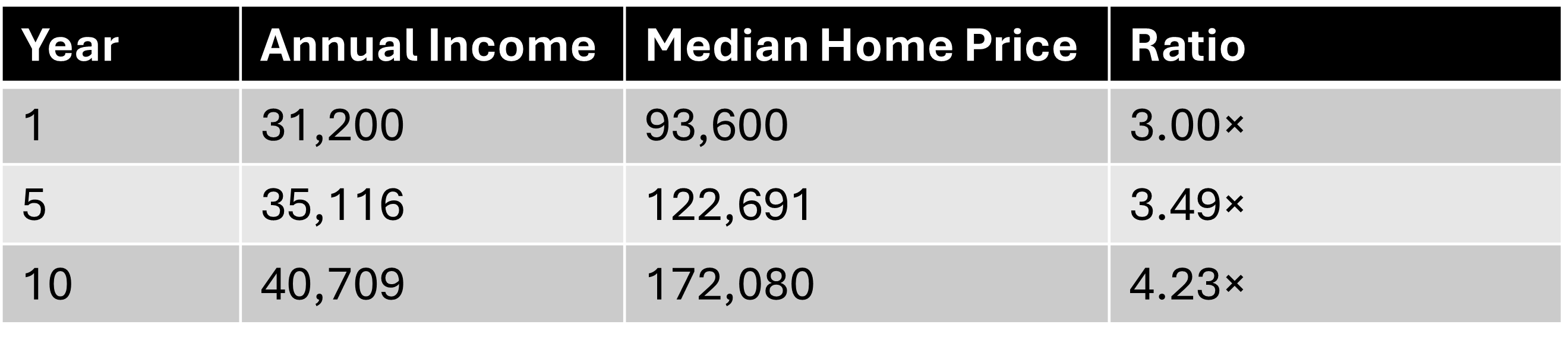

That is not reality. Over the last decade, U.S. wages have grown about two to three percent annually. Home prices, on the other hand, have jumped six to seven percent a year on average, and in the last five years closer to eight to nine percent. That divergence breaks the model.

Apply the thought experiment again with three percent wage growth against seven percent home appreciation, and the gap blows wide open. Incomes creep from $31,200 to around $40,000 in a decade. The $90,000 home sprints to nearly $180,000.

Not only does the home price nearly doubles, so does the required down payment. To avoid carrying PMI on a mortgage, buyers must put down at least 20 percent. That target jumps from about $18,700 to more than $34,000 in just ten years. Wages are not keeping up, and even a family saving up to 35 percent of their income starts to lose ground.

The situation is bad enough without adding in bad numbers. There is no reason to compare today’s minimum wage to today’s median home prices. That is a sensationalist argument, and it distracts from the real measure of affordability. The correct comparison is median income against median home prices. That is the standard lenders use, and it is more than enough to show the true scope of the crisis.

Median household income in 2023 was about $80,600. The median home price in the United States was over $420,000. That is more than five times the median income, far above the old three-times affordability rule. To close the gap, incomes would need to grow at about seven to nine percent per year just to keep pace with home appreciation.

This is the generational divide. Boomers bought homes when wages and home prices tracked one another more closely. Millennials and Gen Z are trying to catch up in a rigged race, where the finish line moves away faster than they can run. Even if you cut wants, save aggressively, and follow every piece of financial advice, you are running on a treadmill.

Is there a solution?

The housing crisis is not the result of one single failure, which means there is no single fix. Affordability has been broken by wages that do not keep up, home supply that has not matched population growth, and a market that has shifted toward building larger and more expensive houses. Any real solution must confront these root causes.

- Wages: Higher wages alone will not solve the housing crisis. In tight markets, wage gains get swallowed up in bidding wars, which push home values even higher. Without a corresponding increase in supply, rising wages simply chase rising prices.

- Supply and demand: The most direct way to restore balance is to increase housing supply. As the population grows, demand naturally rises, and without more homes the competition drives prices up. Zoning reform, faster permitting, and incentives to build smaller entry-level homes would relieve some of that pressure.

- Scaling back home size: Another overlooked solution is to return to building smaller homes. Today, the average American family has fewer than two children, while the average home has about three bedrooms. Families do not need sprawling McMansions as the default. Reviving construction of smaller, affordable homes would add back the missing rung on the housing ladder, giving younger buyers a realistic path to ownership.

Many people will also point to financial solutions. Lower property taxes, better lending programs for first-time buyers, and expanded down payment assistance are all attractive proposals. The problem is that these measures do not fix the underlying shortage of affordable homes. They only shift the financial load around. Until the country is operating on a stable budget and addressing supply head-on, these options remain temporary relief at best.

The math is clear. Wages and housing costs have been out of step for more than fifty years, and every year the gap grows wider. Minimum wage comparisons make for headlines, but the real story is that even median incomes no longer buy median homes. The three-times income rule is broken. Unless the nation addresses wages, supply, and the size of the homes we build, the treadmill will keep running faster and younger generations will never catch up.